All this Hollywood stuff!

This reproduction is intended for purely academic use. It is an unabridged, word-for-word reproduction of the first 8 pages of the above publication "Mr Tompkins in Paperback". No spelling has been changed, and not one word has been added or removed. Each illustration has been reproduced as exactly as possible and in as close a position as possible to its position in the original book. If any of the above is found to be false, then I am at fault in my proofreading. Any comments on this reproduction should be addressed to me:

Jace (John Chamberlain) Harker

jharker@marlboro.edu.

******************************

******************************

It was a bank holiday, and Mr Tompkins, the little clerk of a big city bank, slept late and had a leisurely breakfast. Trying to plan his day, he first thought about going to some afternoon movie and, opening the morning paper, turned to the entertainment page. But none of the films looked attractive to him. He detested all this Hollywood stuff, with infinite romances between popular stars.

All this Hollywood stuff!

If only there were at least one film with some real adventure, with something unusual and maybe even fantastic about it. But there was none. Unexpectedly, his eye fell on a little notice in the corner of the page. The local university was announcing a series of lectures on the problems of modern physics, and this afternoon's lecture was to be about EINSTEIN'S Theory of Relativity. Well, that might be something! He had often heard the statement that only a dozen people in the world really understood Einstein's theory. Maybe he could become the thirteenth! Surely he would go to the lecture; it might be just what he needed.

He arrived at the big university auditorium after the lecture had begun. The room was full of students, mostly young, listening with keen attention to the tall, white-bearded man near the black-board, who was trying to explain to his audience the basic ideas of the Theory of Relativity. But Mr Tompkins got only as far as understanding that the whole point of Einstein's theory is that there is a maximum velocity, the velocity of light, which cannot he surpassed by any moving material body, and that this fact leads to very strange and unusual consequences. The professor stated, however, that as the velocity of light is 186,000 miles per second, the relativity effects could hardly be observed for events of ordinary life. But the nature of these unusual effects was really much more difficult to understand, and it seemed to Mr Tompkins that all this was contradictory to common sense. He was trying to imagine the contraction of measuring rods and the odd behaviour of clocks ? effects which should be expected if they move with a velocity close to that of light - when his head slowly dropped on his shoulder.

When he opened his eyes again, he found himself sitting

not on a lecture room bench but on one of the benches installed by the

city for the convenience of passengers waiting for a bus. It was a beautiful

old city with medieval college buildings lining the street. He suspected

that he must be dreaming but to his surprise there was nothing unusual

happening around him; even a policeman standing on the opposite corner

looked as policemen usually do. The hands of the big clock on the tower

down the street were pointing to five o'clock and the streets were nearly

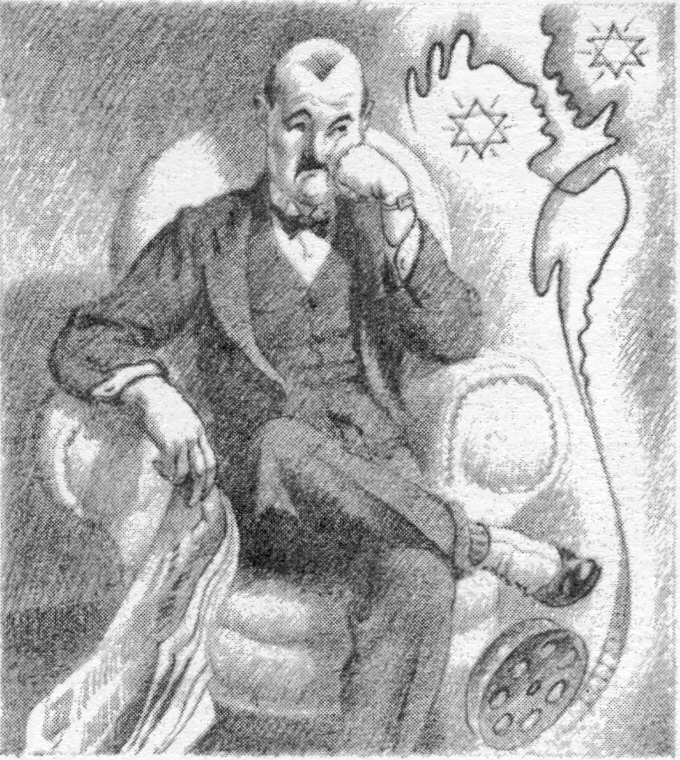

empty. A single cyclist was coming slowly down the street and, as he approached,

Mr Tompkins's eyes opened wide with astonishment. For the bicycle and the

young man on it were unbelievably shortened in the direction of the motion,

as if seen through a cylindrical lens. The clock on the tower struck five,

and the cyclist, evidently in a hurry, stepped harder on the pedals. Mr

Tompkins did not notice that he gained much in speed, but, as the result

of his effort, he shortened still more and went down the street

looking exactly like a picture cut out of cardboard.

Then Mr Tompkins felt very proud because he could understand what was happening

to the cyclist-it was simply the contraction of moving bodies, about which

he had just heard. "Evidently nature’s speed limit is lower here," he concluded,

"that is why the bobby on the corner looks so lazy, he need not watch for

speeders." In fact, a taxi moving along the street at the moment and making

all the noise in the world could not do much better than the cyclist, and

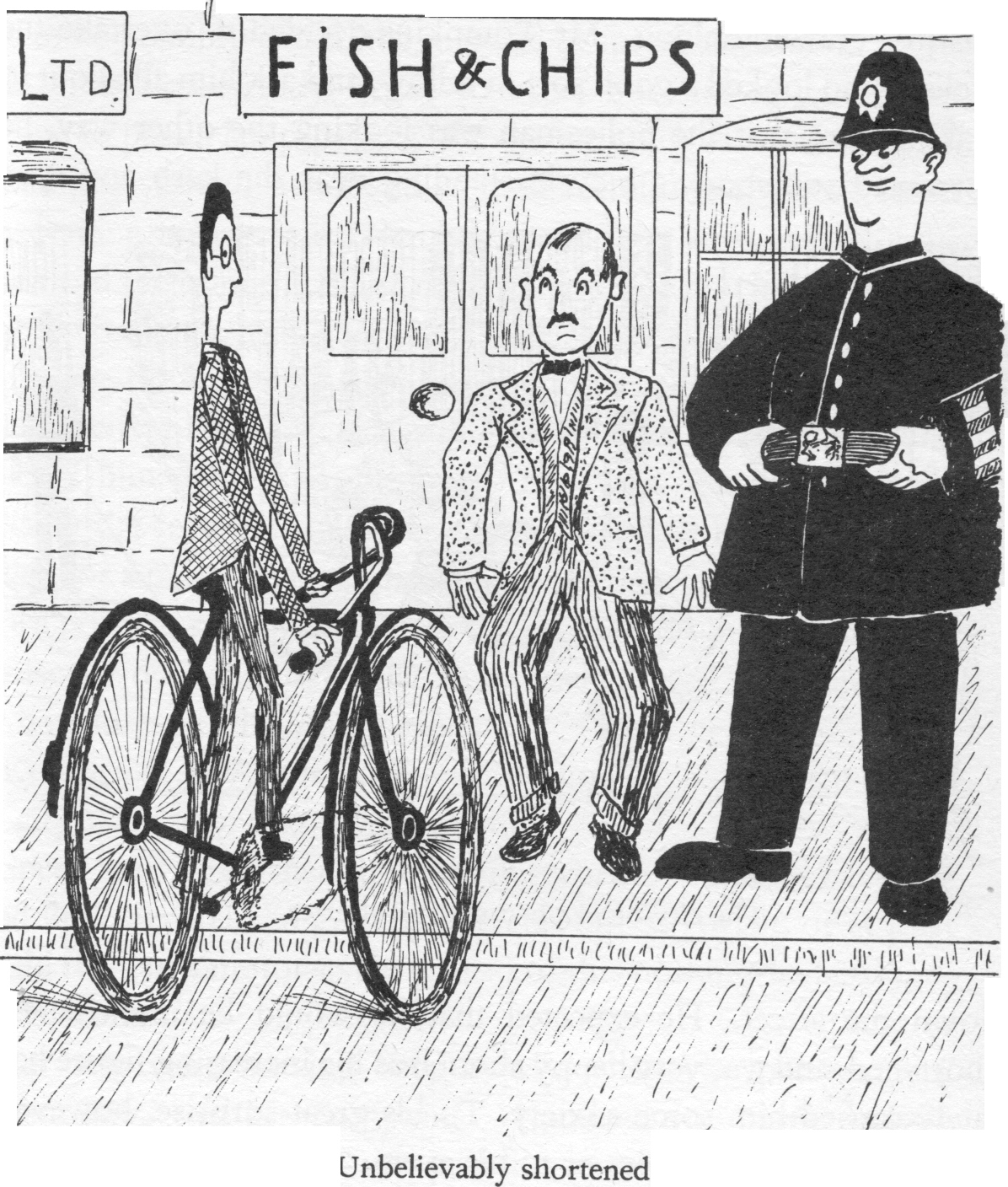

was just crawling along. Mr Tompkins decided to overtake the cyclist, who

looked a good sort of fellow, and ask him all about it. Making sure that

the policeman was looking the other way, he borrowed somebody's bicycle

standing near the kerb and sped down

the street. He expected that he would be immediately

shortened, and was very happy about it as his increasing figure had lately

caused him some anxiety. To his great surprise, however, nothing

happened to him or his cycle. On the other hand, the picture around

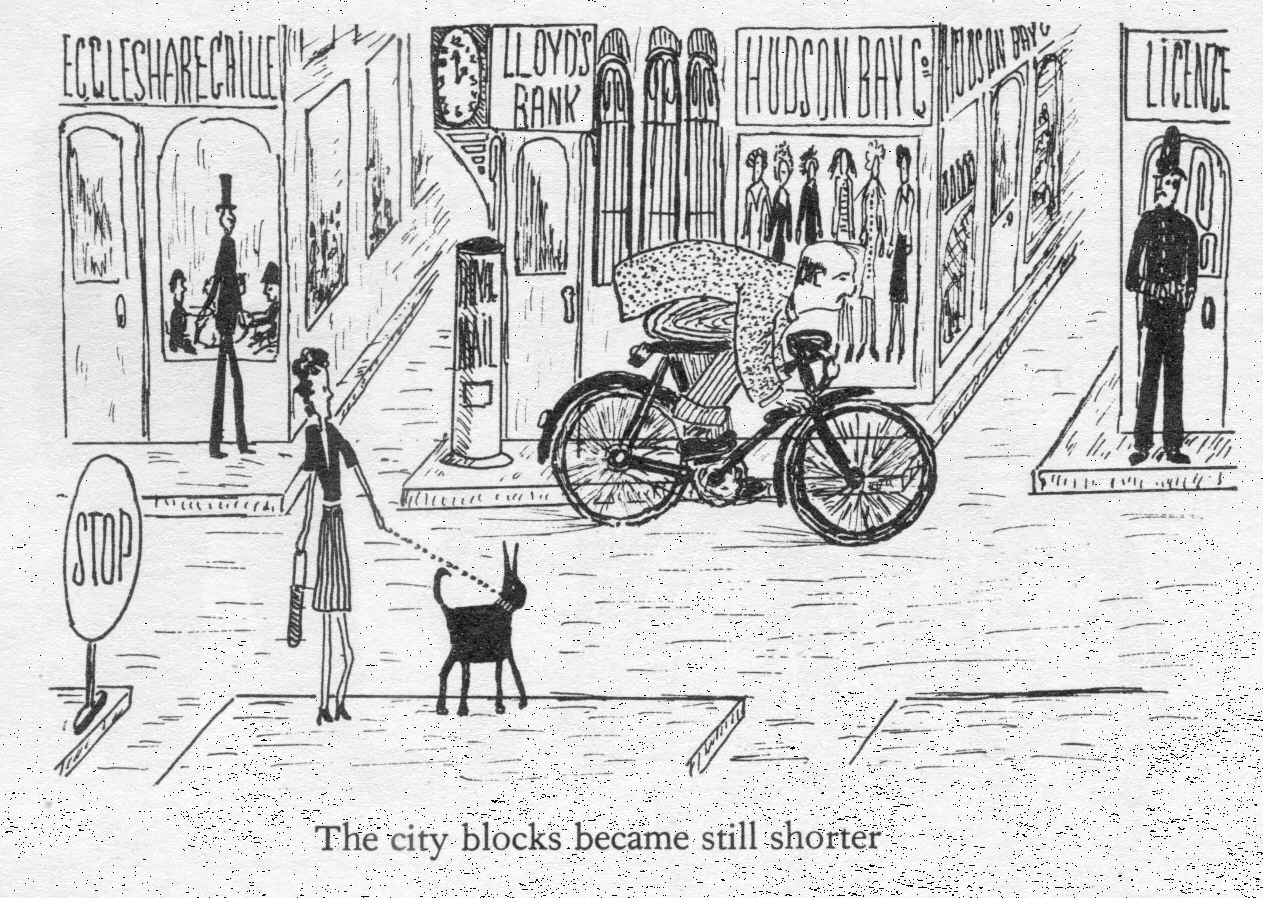

him completely changed. The streets grew shorter, the windows of

the shops began to look like narrow slits, and the policeman on the corner

became the thinnest man he had ever seen.

"By Jove!" exclaimed Mr Tompkins excitedly, "I see the trick now. This is where the word relativity comes in. Everything that moves relative to me looks shorter for me, whoever works the pedals!" He was a good cyclist and was doing his best to overtake the young man. But he found that it was not at all easy to get up speed on this bicycle. Although he was working on the pedals as hard as he possibly could, the increase in speed was almost negligible. His legs already began to ache, but still he could not manage to pass a lamp-post on the corner much faster than when he had just started. It looked as if all his efforts to move faster were leading to no result. He understood now very well why the cyclist and the cab he had just met could not do any better, and he remembered the words of the professor about the impossibility of surpassing the limiting velocity of light. He noticed, however, that the city blocks became still shorter and the cyclist riding ahead of him did not now look so far away. He overtook the cyclist at the second turning, and when they had been riding side by side for a moment, was surprised to see the cyclist was actually quite a normal, sporting-looking young man. "Oh, that must be because we do not move relative to each other," he concluded; and he addressed the young man.

"Excuse me, sir!" he said, "Don't you find it inconvenient to live in a city with such a slow speed limit?"

"Speed limit?" returned the other in surprise, "we don't have any speed limit here. I can get anywhere as fast as I wish, or at least I could if I had a motor-cycle instead of this nothing-to-be-done-with old bike!"

"But you were moving very slowly when you passed me a moment ago," said Mr Tompkins, "I noticed you particularly."

"Oh you did, did you?" said the young man, evidently offended. "I suppose you haven't noticed that since you first addressed me we have passed five blocks. Isn't that fast enough for you?"

"But the streets became so short," argued Mr Tompkins.

"What difference does it make anyway, whether we move faster or whether the street becomes shorter? I have to go ten blocks to get to the post office, and if I step harder on the pedals the blocks become shorter and I get there quicker. In fact, here we are," said the young man getting off his bike.

Mr Tompkins looked at the post office clock, which showed half-past five. "Well!" he remarked triumphantly, "it took you half an hour to go this ten blocks, anyhow -- when I saw you first it was exactly five!"

"And did you notice this half hour?" asked his companion. Mr Tompkins had to agree that it had really seemed to him only a few minutes. Moreover, looking at his wristwatch he saw it was showing only five minutes past five. "Oh!" he said, "is the post office clock fast?" "Of course it is, or your watch is too slow, just because you have been going too fast. What's the matter with you, anyway? Did you fall down from the moon?" and the young man went into the post office.

After this conversation, Mr Tompkins realized how unfortunate it was that the old professor was not at hand to explain all these strange events to him. The young man was evidently a native, and had been accustomed to this state of things even before he had learned to walk. So Mr Tompkins was forced to explore this strange world by himself. He put his watch right by the post office clock, and to make sure that it went all right waited for ten minutes. His watch did not lose. Continuing his journey down the street he finally saw the railway station and decided to check his watch again. To his surprise it was again quite a bit slow. "Well, this must be some relativity effect, too," concluded Mr Tompkins; and decided to ask about it from somebody more intelligent than the young cyclist.

The opportunity came very soon. A gentleman obviously in his forties got out of the train and began to move towards the exit. He was met by a very old lady, who, to Mr Tompkins’s great surprise, addressed him as "dear Grandfather". This was too much for Mr Tompkins. Under the excuse of helping with the luggage, he started a conversation.

"Excuse me if I am intruding into your family affairs," said he, "But are you really the grandfather of this nice old lady? You see, I am a stranger here, and I never...." "Oh, I see," said the gentleman, smiling with his moustache. "I suppose you are taking me for the Wandering Jew or something. But the thing is really quite simple. My business requires me to travel quite a lot, and, as I spend most of my life in the train, I naturally grow old much more slowly than my relatives living in the city. I am so glad that I came back in time to see my dear little granddaughter still alive! But excuse me, please, I have to attend to her in the taxi," and he hurried away leaving Mr Tompkins alone again with his problems. A couple of sandwiches from the station buffet somewhat strengthened his mental ability, and he even went so far as to claim that he had found the contradiction in the famous principle of relativity.

"Yes, of course," thought he, sipping his coffee, "if all were relative, the traveller would appear to his relatives as a very old man, and they would appear very old to him, although both sides might in fact be fairly young. But what I am saying now is definitely nonsense: One could not have relative grey hair!" So he decided to make a last attempt to find out how things really are, and turned to a solitary man in railway uniform sitting in the buffet.

"Will you be so kind, sir," he began, "will you be good enough to tell me who is responsible for the fact that the passengers in the train grow old so much more slowly than the people staying at one place?"

"I am responsible for it," said the man, very simply.

"Oh!" exclaimed Mr Tompkins. "So you have solved the problem of the Philosopher’s Stone of the ancient alchemists. You should be quite a famous man in the medical world. Do you occupy the chair of medicine here?"

"No," answered the man, being quite taken aback by this, "I am just a brakeman on this railway."

"Brakeman! You mean a brakeman...," exclaimed Mr Tompkins, losing all the ground under him. "You mean you—just put the brakes on when the train comes to the station?"

"Yes, that's what I do: and every time the train gets slowed down, the passengers gain in their age relative to other people. Of course," he added modestly, "the engine driver who accelerates the train also does his part in the job."

"But what has it to do with staying young?" asked Mr Tompkins in great surprise.

"Well, I don't know exactly," said the brakeman, "but it is so. When I asked a university professor travelling in my train once, how it comes about, he started a very long and incomprehensible speech about it, and finally said that it is something similar to ‘gravitation redshift’ -- I think be called it -- on the sun. Have you heard anything about such things as redshifts?"

"No-o," said Mr Tompkins, a little doubtfully; and the brake man went away shaking his head.

Suddenly a heavy hand shook his shoulder, and Mr Tompkins

found himself sitting not in the station cafe but in the chair of the auditorium

in which he had been listening to the professor's lecture. The lights were

dimmed and the room was empty. The janitor who wakened him said: "We are

closing up, Sir; if you want to sleep, better go home." Mr Tompkins got

to his feet and started toward the exit.